On a quiet Thursday in Lake Forest, Illinois, the world lost a titan of space exploration. James A. “Jim” Lovell, the legendary NASA astronaut who transformed a near-catastrophic moon mission into one of humanity’s greatest tales of survival, passed away on August 7, 2025, at the age of 97. His death marks the end of an era for a man whose courage, composure, and ingenuity inspired millions and helped pave the way for America’s lunar legacy.

Born on March 25, 1928, in Cleveland, Ohio, Lovell’s fascination with the skies began early. As a young boy in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, he dreamed of flight, building model rockets and gazing at the stars. That passion carried him to the U.S. Naval Academy, where he graduated in 1952, the same day he married his high school sweetheart, Marilyn Gerlach. Together, they built a life that would span 71 years and four children, enduring the highs and lows of a career that took Lovell to the edge of the cosmos.

Lovell’s journey to the stars began in earnest when NASA selected him in 1962 as part of its second astronaut class, the “New Nine,” alongside luminaries like Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin. A naval aviator and test pilot with over 7,000 hours of flight time, Lovell brought a steely calm to the cockpit, a quality that would define his storied career. He flew four historic missions—Gemini 7, Gemini 12, Apollo 8, and Apollo 13—logging nearly 30 days in space and holding, for a time, the record for the most time spent beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

His first mission, Gemini 7 in 1965, was a grueling 14-day endurance test that set a spaceflight record and proved humans could survive long enough for a lunar journey. A year later, Lovell commanded Gemini 12, working with Aldrin to perfect spacewalks critical to the Apollo program. But it was Apollo 8 in 1968 that etched his name in history. As command module pilot, Lovell became one of the first humans to leave Earth’s orbit, circling the moon with Frank Borman and William Anders. On Christmas Eve, as the world listened, the crew read from the Book of Genesis, and Anders captured the iconic “Earthrise” photograph—a pale blue marble suspended in the void, a humbling reminder of humanity’s place in the universe. Lovell later reflected on that moment, marveling at how he could cover the entire Earth with his thumb, a perspective that reshaped his view of home.

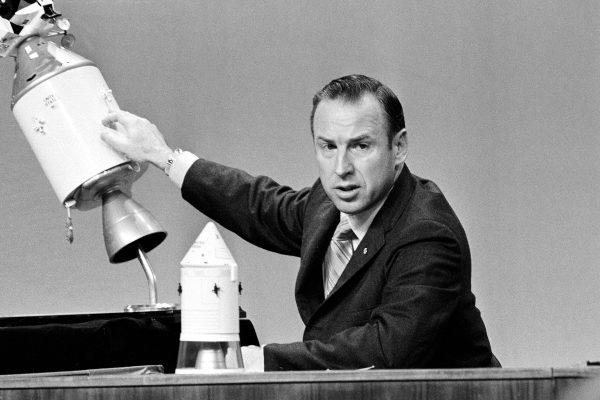

Yet, it was Apollo 13, in April 1970, that immortalized Lovell. As commander, he led a crew of three—Fred Haise and Jack Swigert—on what was meant to be NASA’s third moon landing. Fifty-five hours into the flight, disaster struck. An oxygen tank in the service module exploded, crippling the spacecraft and leaving the crew 200,000 miles from Earth with dwindling power, water, and air. “Houston, we’ve had a problem,” Lovell radioed, his voice steady despite the chaos. The mission’s goal shifted from landing on the moon to surviving the journey home.

What followed was a masterclass in human resilience. Lovell, Haise, and Swigert retreated to the cramped lunar module, Aquarius, using it as a lifeboat in the vastness of space. For four frigid, tense days, they rationed resources, battled rising carbon dioxide levels, and navigated a failing spacecraft. On the ground, NASA’s Mission Control, led by flight director Gene Kranz, worked tirelessly to devise solutions—famously jury-rigging a carbon dioxide scrubber from spare parts. Lovell’s calm leadership and test-pilot precision kept the crew focused, guiding Aquarius around the moon and back to Earth in a daring reentry that captivated the world. The mission, dubbed a “successful failure,” showcased NASA’s ingenuity and Lovell’s unflappable resolve.

Though he never walked on the moon—a regret he carried—Lovell’s triumph over catastrophe earned him greater fame than a lunar stroll might have. “Going to the moon, if everything works right, it’s like following a cookbook,” he told the Associated Press in 2004. “If something goes wrong, that’s what separates the men from the boys.” His story inspired the 1995 film *Apollo 13*, with Tom Hanks portraying Lovell’s quiet heroism. The movie’s line, “Houston, we have a problem,” became a cultural touchstone, though Lovell’s actual words were slightly different. He even made a cameo as a Navy captain, a nod to his real-life rank.

After retiring from NASA and the Navy in 1973, Lovell forged a successful business career, rising to executive vice president at Centel Corp. He co-authored *Lost Moon: The Perilous Voyage of Apollo 13* with Jeffrey Kluger, the book that inspired the film, and ran a restaurant, Lovell’s of Lake Forest, with his family. His contributions earned him the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1970 and induction into the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame in 1993. President Bill Clinton, awarding him the Congressional Space Medal of Honor in 1995, noted that while Lovell “lost the moon,” he gained the “abiding respect and gratitude of the American people.”

Lovell’s personal life was as enduring as his professional one. His wife, Marilyn, who passed away in 2023 at 93, was his rock, supporting him through the uncertainties of spaceflight. During Apollo 8, Lovell honored her by naming a lunar mountain “Mount Marilyn,” a gesture that cemented her place in space history. Their four children—Barbara, James, Susan, and Jeffrey—remembered him as a hero not just to the world but to their family. “We will miss his unshakeable optimism, his sense of humor, and the way he made each of us feel we could do the impossible,” they said in a statement.

Tributes poured in after his passing. Acting NASA Administrator Sean Duffy called Lovell’s courage a cornerstone of America’s lunar ambitions, saying, “He embodied the bold resolve and optimism of both past and future explorers.” Former astronaut Mike Massimino hailed him as a role model, while Ohio Governor Mike DeWine praised his bravery during Apollo 13 as a testament to teamwork and hope. Lovell’s legacy, however, transcends accolades. He showed the world that even in the face of overwhelming odds, human ingenuity and determination could triumph.

As the last of NASA’s “New Nine” and the oldest surviving Apollo astronaut until his death, Lovell leaves behind a shrinking cadre of moon voyagers—only five of the 24 who flew to the moon remain. His life, from a boy dreaming of rockets to a commander steering a crippled spacecraft home, reminds us of what humanity can achieve when pushed to its limits. In his own words, reflecting on Apollo 13’s legacy, Lovell saw it as a testament to “good leadership fostering teamwork to solve a problem.” That spirit, like the man himself, will endure, a beacon for explorers yet to come.