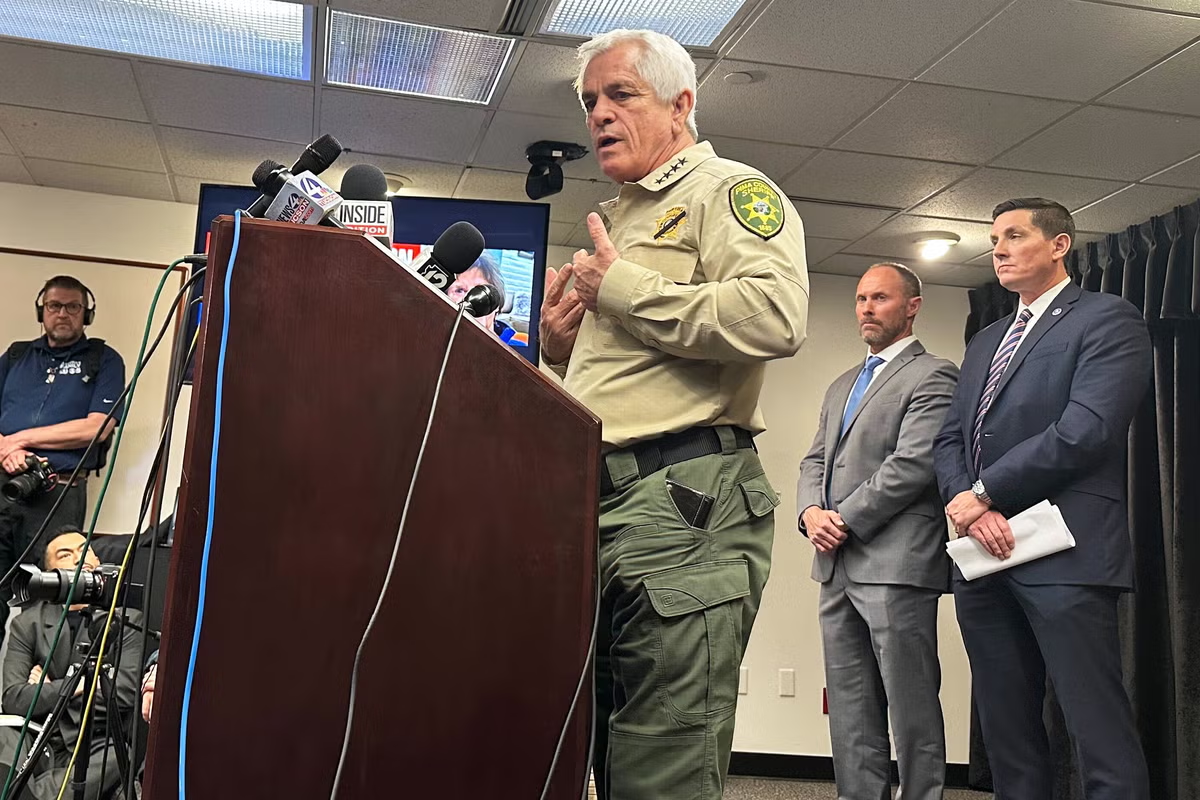

Chris Nanos has spent years in law enforcement, but he admits the intense scrutiny of leading the investigation into the disappearance of Today show host Savannah Guthrie’s mother is new territory.

Since 84-year-old Nancy Guthrie was reportedly abducted from her Tucson-area home, the soft-spoken sheriff of Pima County, Arizona, has tried to balance keeping the public informed with withholding details only the abductor would know. He acknowledges that the approach has not always worked perfectly.

“I’m not used to everyone hanging onto my every word and then holding me accountable for what I say,” Nanos told reporters on the third day of the investigation.

Now entering its second week, Nanos has also admitted missteps, including that he likely should have waited longer before returning Nancy’s home to her family after detectives finished processing it for evidence. During that interval, journalists were able to approach the house and photograph blood droplets that the sheriff said belonged to Nancy.

And critics, including a fellow Democrat, called him out for going to a University of Arizona basketball game last weekend while the victim was still missing.

“That does not look good,” said Dr. Matt Heinz, a Democrat who serves on the county’s government board. “I mean, dude, watch the game at home. Read the room.”

The sheriff’s office didn’t respond to a request for comment on the criticism over Nanos’ appearance at the game.

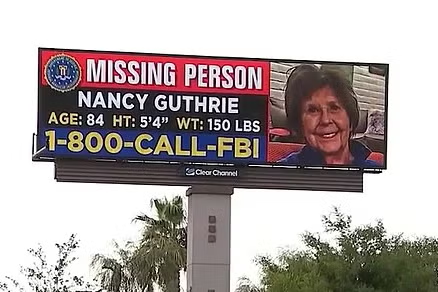

Nancy was last seen at home on Jan. 31 and was reported missing the next day. On Tuesday, authorities released surveillance videos of someone approaching her door wearing a gun holster, ski mask and a backpack, marking the first significant break in the case. The videos — less than a combined minute in length — gave investigators and the public their first glimpse of who was outside Nancy’s home, but they don’t show what happened to her or help determine whether she is still alive.

Soon after the images were released, authorities detained a man during a traffic stop south of Tucson. He was questioned and later released.

Nanos, a native of El Paso, Texas, started with the sheriff’s office as a detention officer in 1984 and steadily rose through the ranks to become second-in-command before being appointed sheriff in 2015 when his boss retired.

Before becoming sheriff, he took part in the investigation into one of Tucson’s biggest tragedies: the 2011 mass shooting outside of a grocery store that killed six people and wounded 13 others, including then-U.S. Rep. Gabby Giffords. At the time, Nanos was leading the agency’s criminal investigations division and, in the days after the attack, was quoted in news accounts as authorities were piecing together a timeline of the attacker’s movements.

As sheriff, Nanos has said his department won’t enforce federal immigration law amid President Donald Trump’s crackdown and that he will use his limited resources to focus on local crime and other public safety issues.

Even so, days before Nancy’s disappearance, Nanos’ office helped investigate an exchange of gunfire between federal agents near the U.S.-Mexico border and a man accused of being involved in a smuggling operation. Authorities say the man, who was shot, had fired at a federal helicopter.

After his appointment as sheriff, Nanos lost the 2016 race to Republican Mark Napier but defeated Napier in 2020. He squeaked by in his 2024 reelection campaign, defeating Republican Heather Lappin by 481 votes in a race that wasn’t without controversy.

Just weeks before Election Day, Lappin, who worked for the sheriff’s department, was placed on administrative leave. In a lawsuit, she alleges Nanos did this to undermine her campaign by falsely accusing her of using her position for personal gain, which Lappin denies.

Heinz, the county board member, said he thinks the late-in-the-campaign administrative action against Lappin likely affected the race’s outcome, given the narrow margin of victory.

As for the investigation, Heinz said he understands how law enforcement leaders want to be transparent with the public about investigations. But he also said it’s “equally important not to get out there in front of a bunch of cameras and talk when there’s not really anything actionable or helpful or of interest.”

Others haven’t been so quick to knock Nanos’ handling of the investigation.

Tom Morrissey, a retired chief U.S. marshal and former chairman of the Arizona Republican Party, said he wouldn’t criticize Nanos, saying it can get complicated when trying to inform the public and still trying not to provide information that might help suspects.

“The perpetrator or perpetrators are watching what law enforcement is doing up close and personal, and it does impact their ability to avoid being discovered or arrested,” Morrissey said.

In an interview Friday, Nanos acknowledged his annoyance with an Associated Press reporter’s questions about the case, saying he was being asked about an element of the investigation that was the FBI’s responsibility and questioned whether the journalist was trying to pit him against his federal partners.

He said he is doing his best to solve the case and demurred when asked to assess how he has handled it.

“I’m going to have people who think I’m doing a good job, and I’m going to have people think I am doing a bad job,” Nanos said. “But that’s what we have elections for.”