A 1974 murder rocked a small Pittsburgh suburb. Police just found the woman’s killer using a 23andMe-like clue

A small Pittsburgh suburb was rocked by a sudden tragedy on March 6, 1974, when police discovered 23-year-old Annette Tokarz had been murdered.

Tokarz’s family, who affectionately called her “Sissy,” found out while watching the nightly news, her younger sister Colette Underwood told The Independent. Underwood was just weeks away from her eighth birthday at the time.

“My mom found out that she died on television,” Underwood said. “I guess there was an unclaimed body at the morgue.”

“I would cry a lot at night because I missed her,” she added. “It was sad.”

Tokarz was “very smart” and had a “heart of gold,” her sister, Sharon Lindner, told The Independent. Lindner recalled that Tokarz’s favorite school subject was history, and the pair often confided in one another because they shared a room.

Police investigated Tokarz’s murder at the time, but they found few answers. For 51 years, the family didn’t know who killed Tokarz. Now, they finally have some peace after Beaver County Chief Detective Patrick Young named a suspect this summer using a DNA analysis method similar to those used by 23andMe and other genealogy services.

The suspect, Walton Sims, has been dead for years — but Young says there’s now enough evidence to take Sims to trial, if he were alive.

“I can’t tell you how much gratitude I have that the police never gave up, and they worked so hard,” Lindner said.

Detective Young found a DNA sample, but it wasn’t enough at first

Young has been in law enforcement since 1994. He retired in 2016 from the Monaca Police Department in western Pennsylvania, then went to the Beaver County Detective Bureau. There, he discovered Tokarz’s case in 2017.

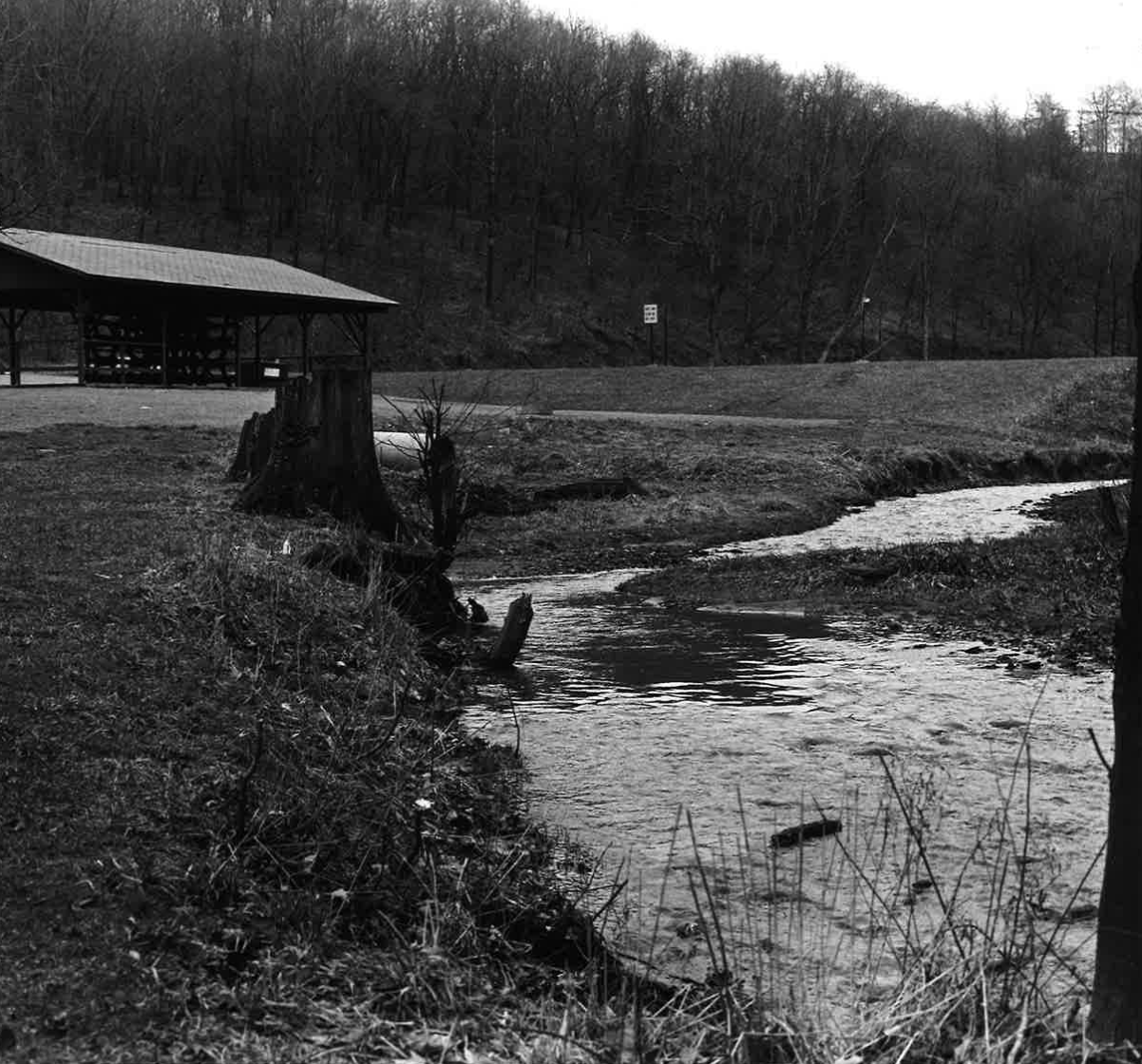

Tokarz was found dead in a shallow creek in Hopewell Township, a suburb about 25 miles northwest of Pittsburgh. She had been “forcefully drowned,” Young told The Independent.

Young was initially left with evidence that didn’t tell him much, like soil samples. Investigators weren’t using DNA analysis in the 1970s, and the first court case that introduced DNA evidence didn’t happen until 12 years after Tokarz was killed.

But the evidence was well-preserved, and Young was able to recover DNA from a stain on a leopard-print coat that Tokarz was wearing when she was killed. Young wanted to run the sample through CODIS, the national DNA database run by the FBI.

However, there was a problem with the sample: analysts were only able to identify eight loci, or specific genetic regions, from the DNA sample. That meant the DNA sample was just one locus short of qualifying for CODIS, Young explained.

As a result, Young couldn’t do a search of the whole database and could only compare his unknown sample to other people whose DNA samples he had.

Top suspect ruled out

Police at the time believed the top suspect was a man named Cornelius McCoy, who told police he last saw Tokarz leaving a bar with a man on the night of her death. That man, Young later realized, may have been Sims.

Young said McCoy “really looked good for it.” Police were never able to gather enough evidence to charge McCoy, and by the time Young was on the case, he had been dead for ten years.

That didn’t stop Young, who tracked down McCoy’s relatives and tested their DNA to compare it with the unknown DNA from the leopard-print coat. But the samples weren’t a match, which meant McCoy was almost certainly not the person who killed Tokarz.

“Who else did I have, really? Towards the tail end of the investigation, on the original investigation, there really wasn’t anybody else,” Young recounted.

Detective Young turns to genealogy

At this point, Young had hit a wall.

That’s when Young decided to take a new approach. Instead of trying to find a direct match, Young wanted to use genealogy to find people related to the person who left their DNA on Tokarz’s coat. To learn about someone’s genealogy, investigators look at a part of the DNA called a single-nucleotide polymorphism. Popular genealogy services like 23andMe and Ancestry also detect single-nucleotide polymorphisms.

This analysis led Young to several people related to Sims, a man whose name he had already seen in Tokarz’s case file.

Sims was Tokarz’s on-and-off boyfriend, Young explained. Sims told police in 1974 he hadn’t seen Tokarz in two months and was in West Virginia when she was killed.

Now, Young needed to determine if the DNA found on Tokarz’s coat belonged to Sims. He died in 2015, but Young said he was able to obtain a court order for the DNA profile of one of Sims’ children.

Young then sent the unknown sample and Sims’ child’s DNA to a paternity lab. There, analysts could determine whether Sims’ child was related to the person who left the unknown sample. If the samples matched, it meant the DNA on the coat likely belonged to Sims.

Thanks to the paternity lab analysis, Young finally had an answer after eight years. Sims’ DNA was a 99.97 percent match.

“At the end of the day, it was all so worth it, just to get the resolution for the family,” Young said.

Underwood says she’s grateful Young cared about the case and brought her family closure.

“I’m so glad that they did figure it out,” Underwood said. “It adds value to the fact that she was a person, and she had a life, and her potential was cut short.”