Night after night, journalist Laura Greenberg ran a bath, pressed play on a tape recorder, and listened to a man describe the heinous murders he had committed.

The voice of serial killer Douglas Gretzler came from behind prison walls as he spoke into the recorder, spilling his deepest, darkest secrets to a woman who hung on every word.

For four decades, Greenberg exchanged thousands of letters and more than 500 hours of audio recordings with Gretzler, one of the most prolific mass murderers in American history, yet one whose case quickly faded from the headlines.

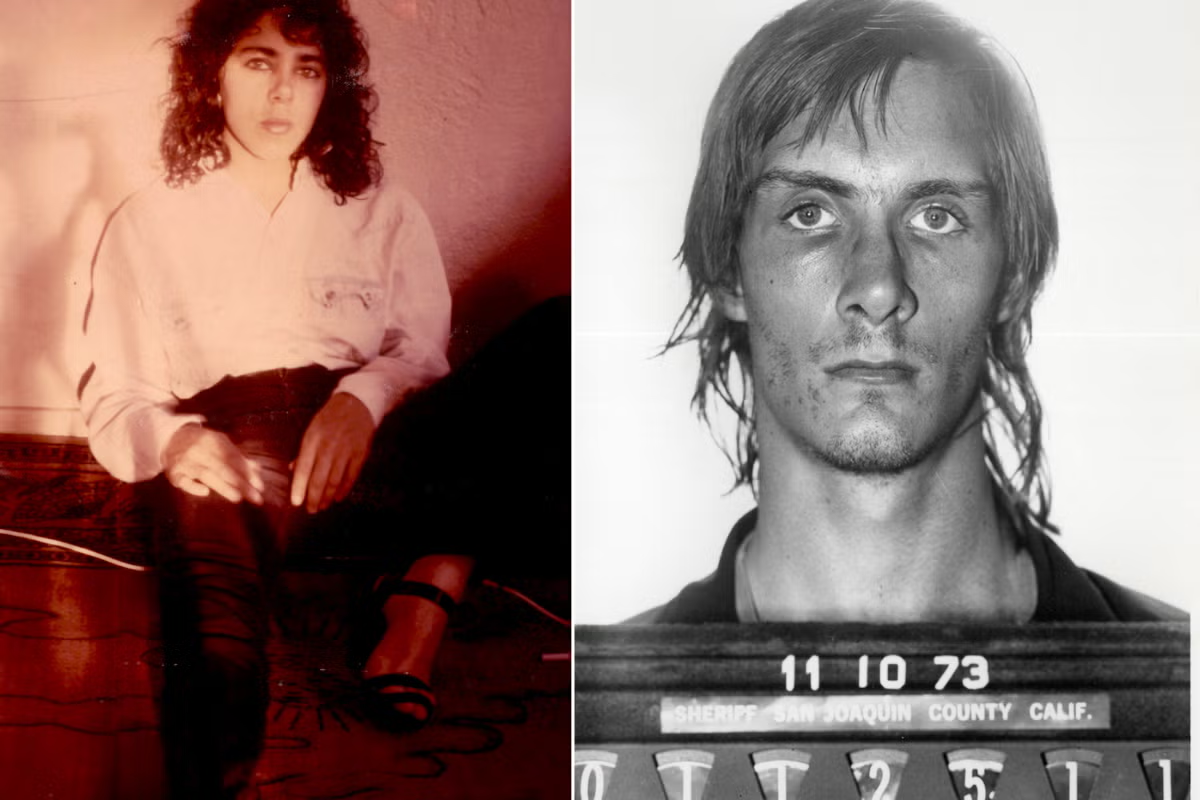

Her goal was to understand why Gretzler, at age 22, and his accomplice Willie Steelman went on a three-week killing spree across two states in 1973 which left 17 people dead, including two children.

“We were both obsessed with the human mind,” Greenberg revealed in an exclusive clip shared with The Independent. When asked what sparked a connection, she said: “He was scary smart. I had to really use my brain.”

The tapes will be heard publicly for the first time Saturday in a new Oxygen documentary, “Charmed by the Devil,” that traces Greenberg’s decades-long pursuit of Gretzler’s motives and the emotional toll of getting dangerously close to a killer.

Over time, the boundaries blurred, giving way to an obsessive, deeply intimate relationship.

“Eventually I thought about him all the time,” Greenberg said in a recent on-camera interview, holding a lock of Gretzler’s hair that he had mailed her. “He had very nice hair actually.”

She added: “He was my secret life and I enjoyed it. I enjoyed having something for myself.”

A road trip and a killing spree

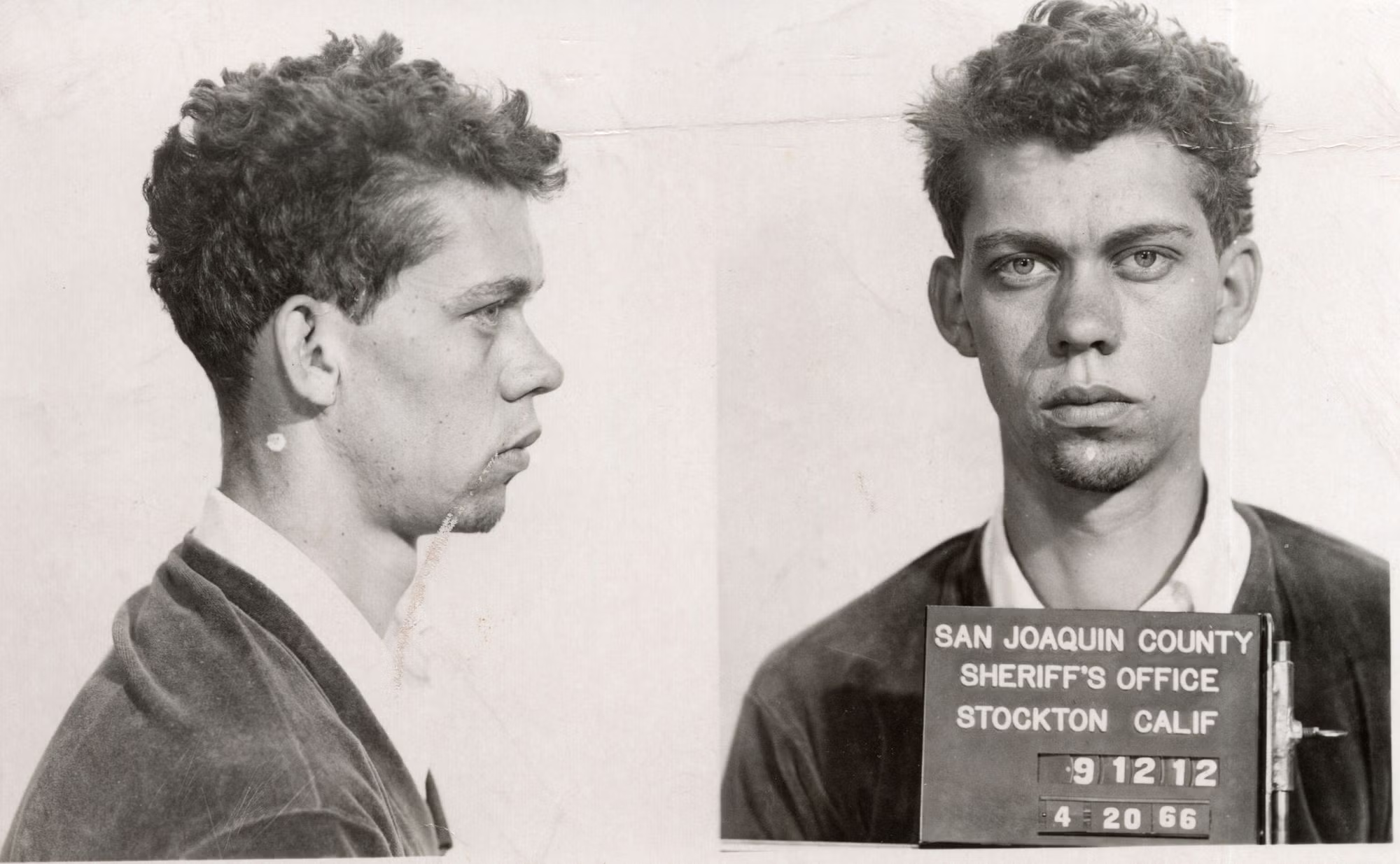

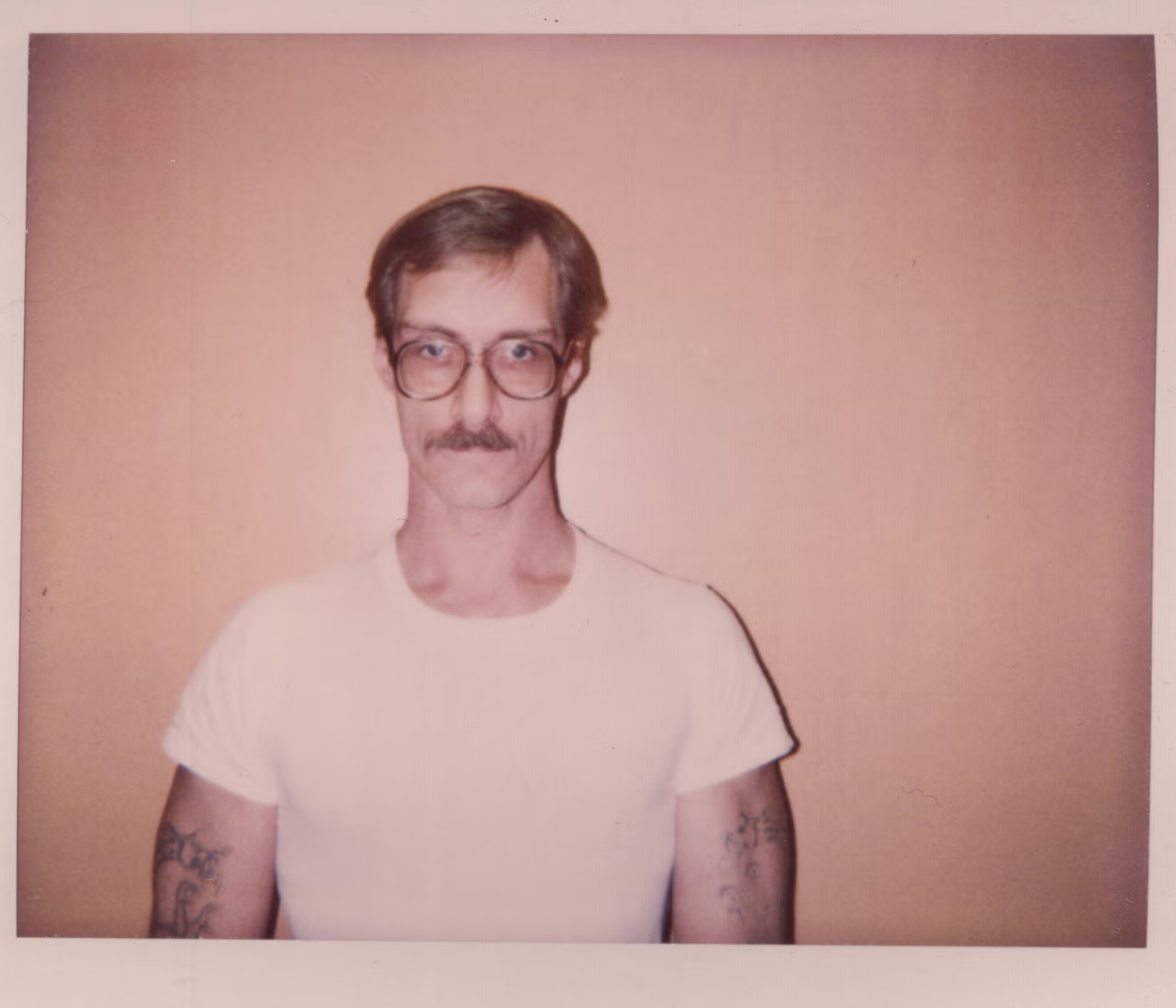

In October 1973, Douglas Gretzler, 22, and Willie Steelman, 28, set off from Denver, Colorado on a road trip to rob people for drugs and money. They had met just a year earlier when Gretzler moved across the country from New York.

Steelman took Gretzler under his wing, teaching him how to steal purses and wallets. The two became close friends with a mutual desire for making quick cash, no matter who got in their way.

They began with petty robberies in Arizona – stealing small amounts of cash, stolen clothes and jewelry. They robbed a couple sunbathing in Globe, Arizona, and stole $5. They picked up a hitchhiker on their way to Phoenix, tying him to a tree, stealing $20, his clothes, and a ring, that they later pawned.

But the violence soon turned deadly.

The pair met up with friends, Ken Unrein and Mike Adshade, and learned that Steelman’s acquaintances, Bob Robbins and Yafah Hacohen, were living at a nearby trailer park so they paid them a visit. Gretzler and Steelman then kidnapped Unrein and Adshade, stole their Volkswagen van and drove to Stanislaus County, California. On October 17, 1973, they stabbed them to death, dumping their bodies and drove off in the van until it konked out.

A few days later, while hitchhiking, Gretzler and Steelman kidnapped a young couple who stopped for them near Petaluma, California. Steelman raped the woman, but eventually both victims were released at an underground garage, where the killers stole another car.

The pair then became concerned that Robbins and Hacohen could connect them to the killings of Unrein and Adshade, so they returned to Arizona to silence them. On the way, they picked up another hitchhiker, killing him and dumping his body in the Superstition Mountains. On October 25, they shot and killed Robbins and Hacohen.

On November 2, again hitchhiking, the pair were picked up by Gilbert Sierra. That night, they murdered him and abandoned his car. The very next day, the men kidnapped Vincent Armstrong who stopped for them in Tucson. But Armstrong escaped and went to the police.

After the failed carjacking of Armstrong, the pair forced their way into a condominium owned by Michael and Patricia Sandberg. They bound and gagged the couple, dyed Gretzler’s hair to avoid detection, and took the Sandbergs’ clothes. Then shot both victims, using a pillow to muffle the sound.

Gretzler and Steelman then fled the state and made their way back to California where they forced their way into the home of rancher, Walter Parkin, forcing him to take them to his nearby store where they stole several thousand dollars from the safe. During the attack, the pair managed to bind and gag seven adults, some of whom were there when they arrived and some who showed up later. They were all killed, along with two children who were shot dead while they slept. Steelman shot one child, and Gretzler shot the other.

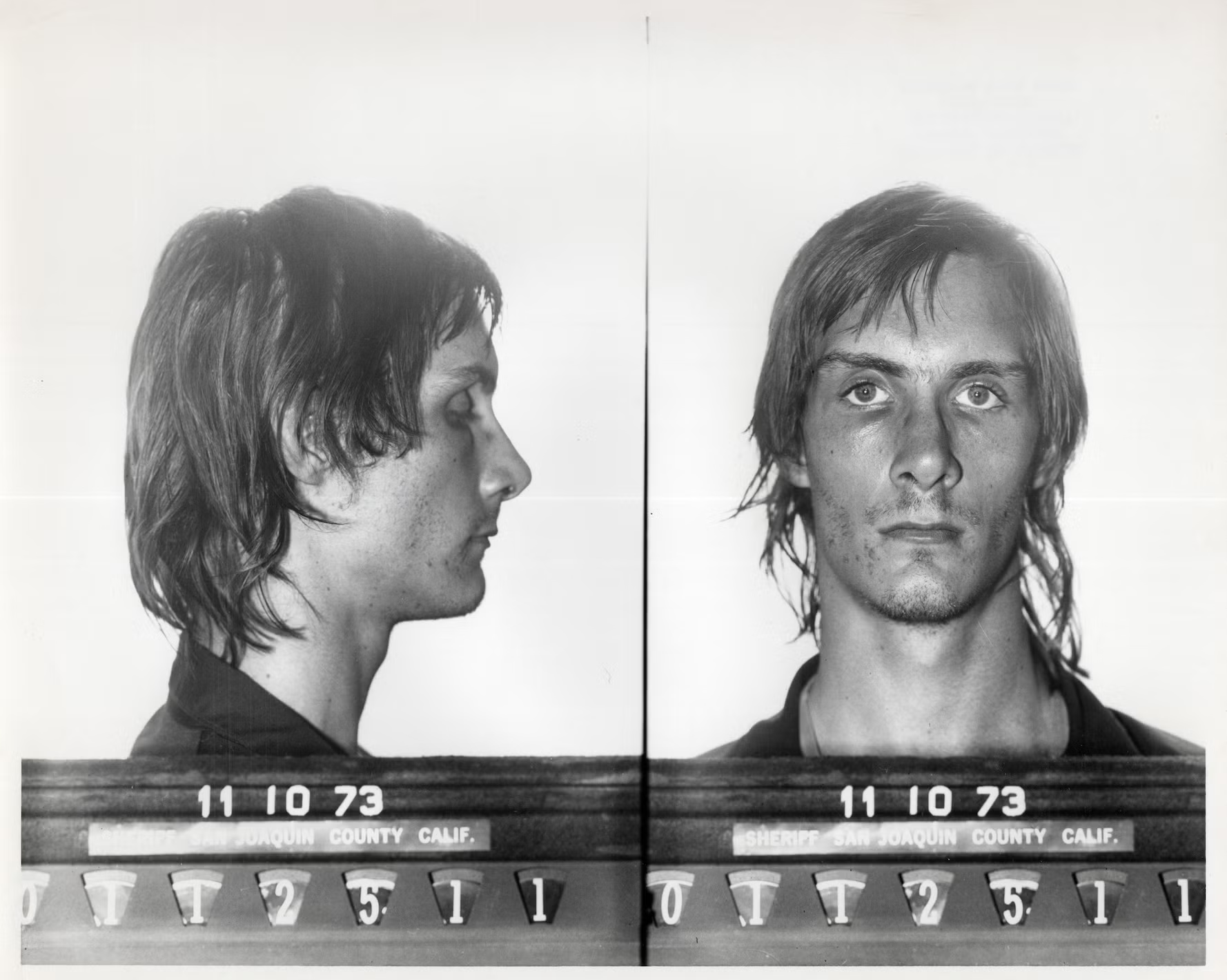

Gretzler and Steelman were arrested days later in Sacramento after a hotel clerk recognized the latter from police photos.

Gretzler confessed to the murders, pleading guilty in California to nine counts of first-degree murder, and received nine concurrent life sentences. Steelman pleaded no contest to nine counts of murder and five counts of robbery in exchange for the kidnapping charge to be dropped. They were both convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

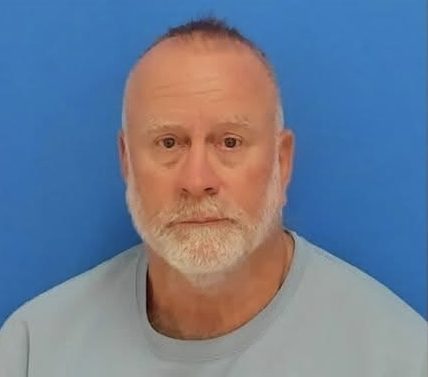

Both men were subsequently extradited to Arizona, which had the death penalty, to face additional charges. In November 1976, Gretzler was sentenced to death for the murders of Michael and Patricia Sandberg.

Steelman was convicted of two counts of murder, one of kidnapping, two counts of robbery, and one count of burglary. He was sentenced to death, plus 80 to 95 years for the kidnapping of Vincent Armstrong, and the burglary and robbery of the Sandbergs. He died of cirrhosis in 1986.

While on death row in Arizona, Gretzler shut down. For 12 years he didn’t speak about the murders.

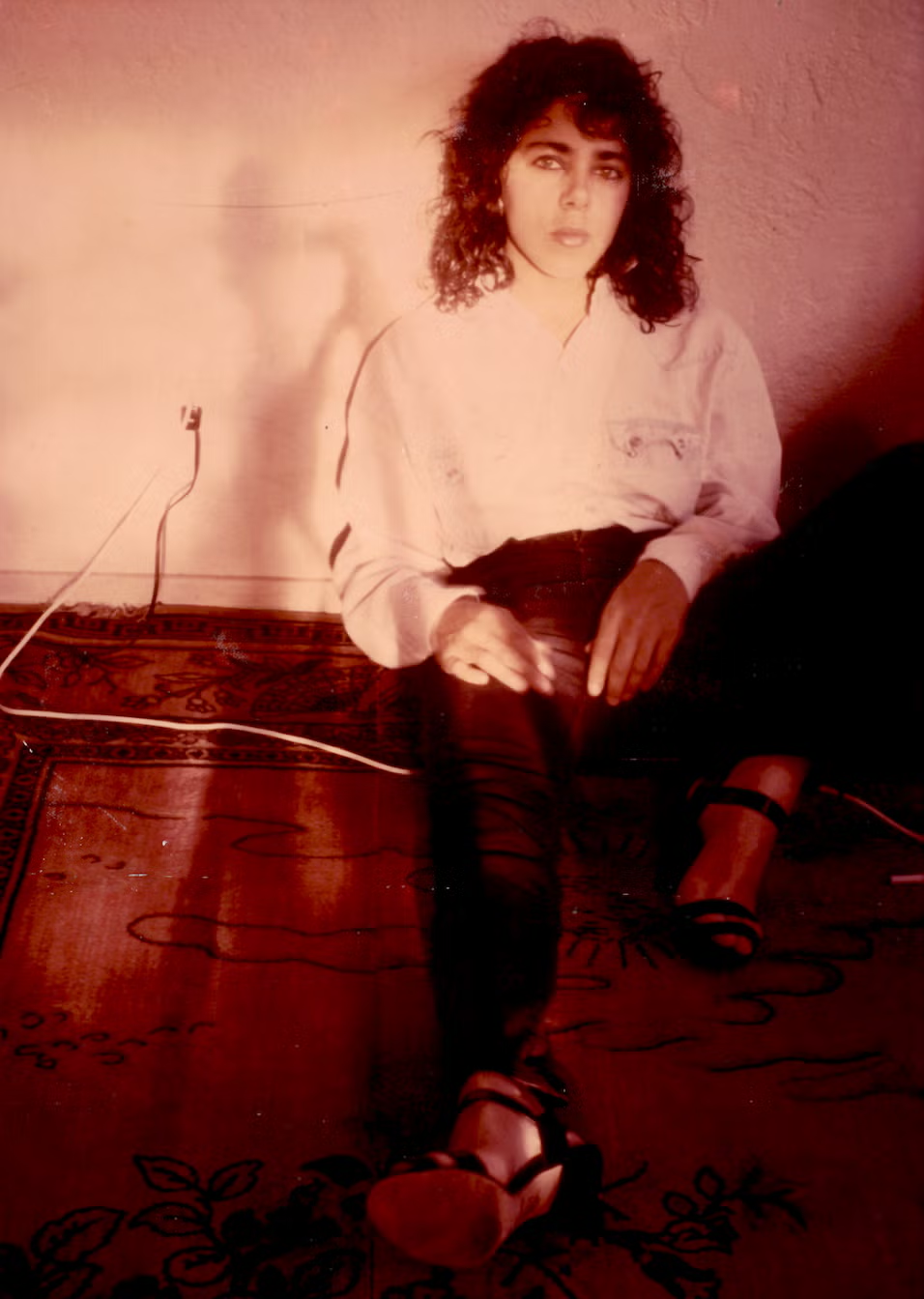

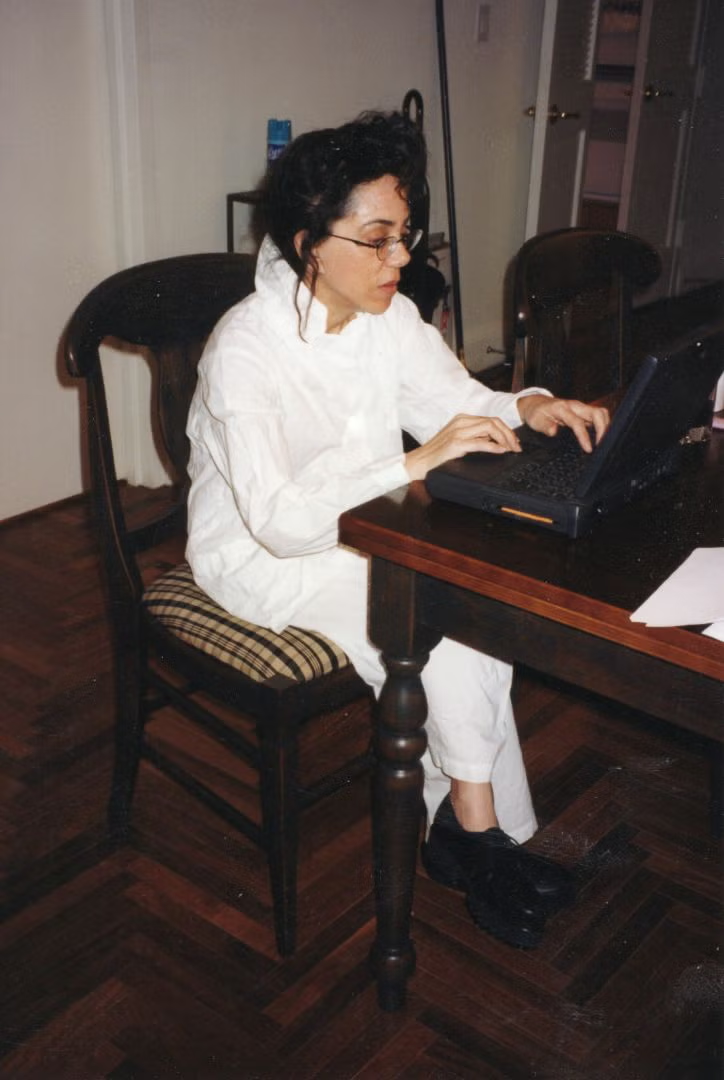

In 1988, Greenberg, was a reporter for the City Magazine in Tucson who had found her niche on the crime beat. When she got a tip about two men on death row, whose story had long disappeared, she wanted to know more.

“It was the biggest mass murder story in 1973,” Greenberg said. “But as quickly as the murders unfolded, they were completely forgotten.”

She was fixated on the unanswered question at the center of the case: why? So she sent a letter to Gretzler in prison asking him that very question.

“I wanted to know how could a man kill 17 people,” she said. What followed was many interviews at Florence State Prison. Gretzler told Greenberg that he had not had a single visitor until she came in 1988.

At first, their meetings took place with a glass partition between them and other inmates around. After a year and a half, they were granted contact visits, which meant they could sit in a room with a table and two chairs.

“I went and visited Doug 350 times in prison,” Greenberg says in the documentary. “We wrote hundreds of letters and we recorded 500 plus hours of audio tapes. I wanted to understand the monster.”

Blurred lines

During her first visit to the prison, Gretzler told Greenberg that her letter had intrigued him.

They then bonded over their similar upbringings. They were both originally from New York, with Greenberg from Queens and Gretzler from the Bronx.

“He started to open up more and that’s when I realized that neither one of us ever fit in anywhere,” Greenberg said. “That was our glue.”

She explained that she wanted to know what made him kill, and why he had killed a child. “Can’t get much colder than that,” Greenberg explains in the documentary, adding that she was “disgusted” but removed herself from a “feeling state” in order to get information from him.

Gretzler blamed those killings on his partner but added that it didn’t take much for him to do something so heinous.

“Because Willie told me to,” he told her. “It didn’t take me a lot to kill, Laura. I didn’t have standard roadblocks in my mental roadway that would have stopped me from killing.”

After their prison meetings, Gretzler asked if he could also share his story on audio tapes. So Greenberg would send a recorded tape of herself asking questions and he would respond.

The killer details his family’s dark past in the recordings. Gretzler told her about his brother, Mark, his father’s favorite and could do no wrong – until he broke into school and stole test answers.

The family arranged a meeting to talk about getting Mark help. But he didn’t show up, and when Gretzler went to get him from his bedroom, he found his teen brother dead of a self-inflicted gun shot wound.

“When my brother committed suicide, my father just shut me out,” Gretzler can be heard saying on one tape. “I was made to feel like my father wished it was me who died.”

But despite decades of conversations, Gretzler remained elusive on the motive behind the litany of murders.

At one point he told Greenberg: “I wanted to show [my father] that I was cool, cold and f***** in the head as he was.”

Still, the interviews continued but the tone of the tapes became more personal, and flirtatious. “We started chit chatting about everything,” Greenberg recalled. “I would fill up the bathtub and I would listen to him talk to me about murder.”

Gretzler asked her for a lock of hair, and sent one back in return. He asked the journalist for pictures of herself in a bathing suit. She obliged.

At one point, the serial killer told her in a recording: “I love you. And I am still in love with you.”

“I called him the romantic serial killer,” Greenberg said. “He had a romantic streak that was insane.”

She continued to date men outside of her relationship with Gretzler, but years passed before she settled down.

“I just felt like we were in a different type of relationship, one that was in some ways more important than my romantic ones, which I had been a failure at,” she said. “I blur lines in every relationship I’ve ever had.”

When Greenberg got married to man named Kevin, Gretzler was not happy, she said. “I’m just incredibly jealous of him,” Gretzler says on the tapes. “Incredibly jealous.”

On June 3, 1998, Gretzler was executed by lethal injection. Greenberg joined some of his family members at the prison.

She says she does not regret their close relationship. “Very few people really knew me,” she said. “Gretzler knew me.”

But was she in love with a serial killer?

“There were 17 dead people that stood between us – and that’s a lot of people,” she said. “But I still miss him.”

Charmed by the Devil premieres December 13, at 9 p.m. ET/PT on Oxygen.